There is an amazing amount of shit meditation advice for beginners floating around. I know this because I talk to people about meditation, and they tell me why they don’t like meditating, and their reasons indicate that they’ve been given dumb ideas about what meditation has to be.

“I can’t stop myself from thinking.” Cool, you actually don’t have to. “I can’t make the time.” Being present for one full breath can be a powerful practice, if you remember to do it reasonably often. “I’m finding it really frustrating and stressful.” That's not how it's supposed to feel. Try a different technique?

Thus, this post, containing most of the things I wish I’d been told before establishing a meditation practice.

In brief

Here is a terrible set of beginner meditation instructions: “Sit up straight in a lotus pose, whether or not you like doing that. Do whatever you need to do to shut down your mind from wandering or changing. Suppress emotions, try to stop thoughts. Do everything you can to install a meditation object as the center of attention. Make yourself calm by force. Do this until you are an enlightened being, for 30 minutes at a time.”

Here is a better set of beginner meditation instructions: “Settle in a posture that, for you, provides a good compromise between comfort and alertness. Open yourself to the detail of your experience. Allow yourself to be interested in, and receptive to, the rich, particular texture of what’s happening—look beyond the concept of experience into what’s actually going on with your mind, and senses, and emotions. Don’t argue with what’s there. If you wish, bring your attention to a meditation object, like a mantra, or the flow of your breath, and notice how this tends to make your experience more collected and calmer. Orient towards whatever brings relief, wakeful relaxation, and pleasantness. Do this for anywhere between thirty seconds and ninety minutes.”

The rest of this post will be an elaboration on why the latter set of instructions works better.

Broad awareness is often better and easier

One of the most common beginner meditation instructions is, “focus on your breath at the tip of the nose.” I think this is a terrible beginner instruction.

Quick vocabulary clarification. For the sake of this discussion, “attention” is the little thing you’re focusing on—say, these words specifically. “Awareness” is everything you could direct your attention towards—so, the full page of text, beyond it the full visual field, body sensations, ambient sound, feelings, thoughts, any other bits of potentially accessible mind-stuff.

For the vast majority of people, it is easier, more calming, and more natural to maintain a broad, expansive awareness than it is to narrow awareness down to a few sensations.

You can test this right now! Take a second to look away from this text, and allow your awareness to become as broad and inclusive as possible—notice the fullness of your peripheral vision, the richness of body sensation, the temperature in the room, the air around your head. Then, for contrast, try to narrow your attention to a tiny point while shutting out everything else.

You will probably find it more pleasant to be expanded. If so, consider maintaining a somewhat broad awareness during meditation! When you’re meditating on the breath, you can feel the multifaceted sensations playing out within the whole body. If you’re repeating a mantra, you can feel how it reverberates in the whole space of mind. And so on.

There are a few select meditation techniques that more or less require very focused, contracted attention. But most of the time, you’re better off with a sensitive, broad, wakeful awareness that fills the whole body, and, if your eyes are open, the whole visual field. (Expanding awareness, on its own, can be a powerful practice: check out this and this.)

Collectedness, not concentration

Many people hear that meditation involves concentration, and they assume this means a state in which nothing but the meditation object—say, a mantra, for example—enters consciousness. There are no thoughts or body sensations or emotions intruding. Just the desired thing, nothing else.

This is extremely hard to do for most people. It is also extremely hard to do for meditators! This is a specific kind of concentration that is sometimes called “one-pointed,” which requires specific training, and it’s usually not necessary.

The quality that you’re looking for in most meditation is, I think, best described as collectedness. You can think of this as the opposite of being scattered. Your mental activity is being naturally organized by the intention to stay present in the moment, rather than the intention to, say, continue a Twitter argument in your head. This is not at all exotic—it’s probably what most people intuitively mean when they think of “being present.”

Just try to get there, and gently return to it after you get knocked off course. Note that collectedness doesn’t preclude letting thoughts emerge. You can have thoughts quietly bubbling away in an expansive, collected mind, and this is actually nice.

Collectedness is a skill that you can practice, and this is a lot of what meditation ends up being about. But it’s also affected by your disposition, regardless of your meditative skill. Depending on the attitude you bring to practice, you can either hurt or help your collectedness a lot, right away.

For example, it’s hard to remain collected when you don’t enjoy what you’re doing. So, you should probably pick a meditation object and a posture that you enjoy. (More on that in a second.)

It’s also hard to remain collected when you have a self-critical attitude: so, chastising yourself for not concentrating hard enough is directly contrary to the mission.

And, fundamentally, a critical attitude towards the current situation is detrimental to collectedness—it’s much easier to focus when you accept your current thoughts and emotions. Thus the most powerful meditation prompt I’ve ever heard, from Loch Kelly: “What is here now if there's no problem to solve?”

Find the meditation object that is most pleasant and easy for you to focus on

Pretty much no matter what your goals with meditation—whether you want to make your mind a nicer place, or reformat your whole experience—it’s helpful to begin by generating a calm and pleasant but wakeful state.

And an inconvenient truth is that there is a huge amount of variation in what beginning meditators find pleasant to focus on. If you’re not used to meditating, it’s likely that you will find one of these five to be intrinsically quite pleasant to focus on, and the rest, meh:

The pleasant feelings that arise in the bodymind when you think of someone you’re fond of

A mantra, silently repeated as you breathe out (can be any phrase in any language, whatever you find resonant)

The entirety of your fascinatingly variable bodily sensations (for example: the existence of your toes, the feeling of oxygenation as you breathe, the subtle tension in your face)

The visualization of a personally resonant symbol, person, etc

Nothing in particular, just, like, whatever’s there

It would behoove you, if you’re getting started, to spend 3-4 days experimenting with each of these objects. Then, go with the one that gives you the greatest sense of relief and relaxation. This is supposed to be nice. While your practice might eventually expand to the point where you’re purposefully courting difficult sensations and emotions, there’s no need to start that way.

This is true even if you want to eventually move onto a different kind of meditation object. For example, mostly I practice in a Dzogchen-influenced style, where the meditation object is “whatever’s happening right now / the ground of being itself.” But this was much easier for me after some practice with mantras and body sensations, which were more intuitive to me as a beginner.

Receptive, not prescriptive

As previously mentioned, a critical attitude towards the current circumstances makes it harder to achieve mental collectedness. Going further: when people have a bad time with meditation—anything from a frustrating time to a really destabilizing time—it tends to come from prescribing experience rather than being open to experience.

Of course, when you’re meditating, you are intending for experience to be different. Like, you want it to be calmer. But there’s a highly relevant difference between engineering the conditions for calmness and trying to force your mind to be calm.

Before you begin meditating, it’s really helpful to adopt a permissive attitude towards your current state: however I am right now, it is fine. I like reminding myself that I don’t need to do anything to receive sensation—the universe will keep on being the universe, and interesting data will come to me, I don’t have to force anything. This can bring about a mental unclenching that enables deeper and more satisfying practice.

Posture is a practical matter, not a punishment

Some meditation traditions are absolutely militant about posture. Like, if your spine isn’t in perfect alignment, with your chins tucked, and hands in a mudra, you’re not actually meditating. As far as I can tell, this is just not true. It’s directly contrary to the experience of many meditators I’ve met who have had dramatic results without being super rigid about posture—including me!

Different postures will do different things for you. It’s true that an upright, elegant posture will tend to promote wakefulness and focus, and often I find this to be the best posture for my practice. But if you’re a person with a very intense, focused mental environment by default, it’s possible that leaning back could make it easier to achieve mental collectedness—this has been true of my wife. Similarly, if you’re really dreamy by default, there’s a more mentally intense way to meditate: standing up. Sometimes, I do standing meditation if I want to contact emotions that I’m tempted to suppress by cocooning myself in dreamy coziness. On the other end of the spectrum, there are entirely legitimate lying-down meditations where you’re allowed to get sleepy.

I’d recommend, to anyone, trying different postures, just like trying different meditation objects. What makes you feel open, wakeful, alert, comfortable but not drowsy, sensitive to the body, stable but not rigid? Don’t take anybody’s opinion on how you should sit, find what works for you. Take a moment to make little micro-adjustments. Note that different things might work at different times, and that different postures can help you explore different states of mind.

Also, moving is a posture. Some of my most powerful practice has been walking. Corey Hess, a teacher I have a high opinion of, recommends spontaneous movement—just letting your body do what it wants to, while keeping a state of full-body awareness—as a meditative practice, and I’ve found it fascinating at times.

Above all, do not make this miserable.

Curiosity, not homework

I notice that many people who say they want to meditate, but don’t, assume that they need a slightly longer amount of time than whatever their amount of free time is. That is incorrect.

Meditating for a longer period of time is more psychoactive. I find that, often, sitting starts to get really interesting after 45 minutes. But what’s far more important than time expenditure is having a curious, receptive attitude. If you make the wholehearted attempt to be thoroughly alive to your experience for one full breath, and you curiously investigate what this does for you, that’s much better than 20 minutes of grindy, homework-y practice that you’re not really there for.

Moreover, adopting this curious, receptive attitude throughout your life is what will make your practice actually meaningful. Sitting for long periods of time is not particularly useful if you don’t make practice part of your way of being. See if you can drop into a state of presence here and there throughout the day. Get into the habit of asking, “what’s my experience like right now,” and noticing the quality of your consciousness, beyond thoughts and stories. Especially do this during moments you find enjoyable. (My friend Hormeze has a great prompt for meditatively listening to music: pretend the music is rain, and you are a puddle.) Understand that you can get much more life for free by doing this. As Shinzen Young once wrote: “You can dramatically extend life—not by multiplying the number of your years, but by expanding the fullness of your moments.”

If you’re looking at practice as the time you have to blandly sacrifice so that you can be a Chill Meditator Person with a more persistently neutral facial expression, you’re already losing. That’s engaging in the kind of self-aggression that gets in the way of being alive—precisely the problem that meditation is supposed to address, rather than exaggerate. Meditation shouldn’t be a venue for staging another fight between you and how you’re supposed to be.

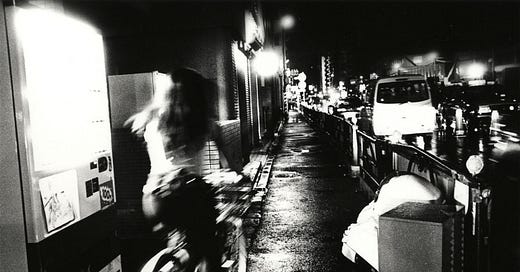

Photo credit goes to Daido Moriyama.

This was probably the most helpful thing I’ve read on meditation. Thank you

This post shows up right on time when I just came back 3 days ago from my 10-day vipassana meditation when I was embarking meditation for 6-8 hours a day for 10 days.

I couldn't agree for more. I wish I could have read it before the retreat, but I've learned a lot during the process at the monastery. I think you've made the process much easier for new people to understand, but again, only by practicing it so more people can relate.

Some key takeaways for meditation:

- It is a hard habit to start and sustain unless you have experienced what does it feel to be enlightened. To feel oneness and wholesome in yourself. This takes a lot of effort. You need to enjoy the process.

- For me, mindful walking is the quickest way to be engaged and focused into the present moment. Just be aware the way you walk and walk very slowly.

- When I was first starting it, my teacher monk only told me to observe my thoughts and listen to my abdomen by breathing but without forcing the way I breath, e.g. deep inhale/exhale. Then, I realized it was easier if I listen to my breath compare to abdomen. So, I sticked to the breath, and it works!

- Then, I expanded my awareness into the body scan. It's basically touching your part of body by using your mind. This is definitely hard to digest when the monk told me for the first time. Only by practicing it I could notice it eventually, and it allows me to feel the present moment with more richness as now I can feel the part of my body.

- Do not force anything to happen. Since I've felt what does it feel to be enligthened (peaceful, calm, empty), sometimes I tried to force my act to get calm faster, such as playing around with how long do I inhale/exhale, the posture of my body, forcing awareness to the room and temperature, etc, but it didn't work that way. Let it come naturally without forcing anything to happen because there's nothing wrong and nothing to be fixed or improved. The more you try to fix/improve, the less calm you are. 100% agree with Loch Kelly: “What is here now if there's no problem to solve?”

- Make sure to Begin Again. Ability to begin again is necessary during meditation. Sometimes our minds are drifted away. We lost in thoughts for God knows how long. Begin again shows a willingness to return to the moment without judgement and disappointment with a mind that is truly free of the past. Begin again is also an ethical force. It’s a foundation of forgiveness. We should forgive our pasts. It builds the resiliency of our minds.

I wish the monk explained it more clearly based on this post, rather than told me to just sit and observe my thoughts without judgements. It took more time but I learned the hard way :)